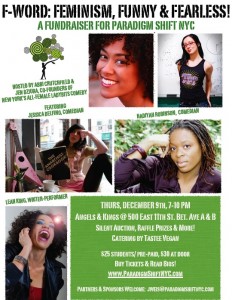

This Thursday, December 9th, from 7 to 10 pm, head to Angels & Kings @ 500 East 11th Street between Avenue A and B for “F-Word: Feminism, Funny & Fearless! A Fundraiser for Paradigm Shift NYC.” You don’t want to miss this incredible event hosted by Abbi Crutchfield and Jen Dziura, featuring Jessica Delfino, Leah King, and Hadiyah Robinson. Don’t forget, this is a fundraiser for Paradigm Shift NYC! Tickets are $25 dollars prepaid/for students and $30 dollars at the door; . If you can’t make it, please donate – we need your support!Check out what these amazing women had to say when I interviewed them about the upcoming performance, activism, and female empowerment: This Thursday, December 9th, from 7 to 10 pm, head to Angels & Kings @ 500 East 11th Street between Avenue A and B for “F-Word: Feminism, Funny & Fearless! A Fundraiser for Paradigm Shift NYC.” You don’t want to miss this incredible event hosted by Abbi Crutchfield and Jen Dziura, featuring Jessica Delfino, Leah King, and Hadiyah Robinson. Don’t forget, this is a fundraiser for Paradigm Shift NYC! Tickets are $25 dollars prepaid/for students and $30 dollars at the door; . If you can’t make it, please donate – we need your support!Check out what these amazing women had to say when I interviewed them about the upcoming performance, activism, and female empowerment:

1) What should people expect from “F:Word: Feminism, Funny, and Fearless!”?

Jessica: People should expect to encounter a whole room full of smart, fun, terrific women, some of them named me (I’m a gemini) who are slightly embarrassing themselves on stage for the benefit of a laugh, and also, some really confident dudes. I also imagine it will be a good place to learn, be inspired and possibly even get laid by another consenting adult.

Abbi: Firstly, a frightfully fast and furious frenzy of freaky femme fatales! For friendly fun, fear not! Five fabulous females share feel-good fairy tales for a few dollars! Finally, forty flopping flounders fight fifty flying fish for a fiefdom of figs. Phew! (Also a raucous night of comedy, and there might be more than five of us).

Hadiyah: I think everyone should expect a good time. The line up is a mixed bag of styles and there’s going to be something for everyone.

Jennifer: Well, to begin with, those of us who are menstruating are going to tell jokes from a hut offstage, because we are impure. Also, we are obviously going to be very bitchy.

Leah: It’s wild to me that the word ‘feminism’ has become such a loaded label with varying definitions. My mom has always told me that she is an Original Feminist, and that it’s all about empowerment, independence and embracing individuality. She’s also a hilarious woman full of humor and spunk. I think that “F:Word: Feminism, Funny, and Fearless!” is a way to reclaim and celebrate the diversity of women – all of our senses of humor, struggles, joys, and reasons to be proud!

2) Comedy is a great way to publicly discuss important issues and taboo subjects, which helps raise awareness and opens up space for important conversations. How would you describe the relationship between comedy and activism in your work?

Jessica: They make sweet love nearly every night, in front of a room full of people and they don’t care who’s watching. Whether it’s subtle, subliminal or in your face, my comedy always touches on issues that I consider to be important, first as a human, and second as a woman. It can be tricky to marry activism and comedy but if I wanted a job that lacked those things, I would have gotten a job as a bank teller, not a joke teller.

Abbi: You’re right that comedy can raise awareness, but the important conversations better not happen while I’m on stage. Show some respect and keep it down, activists! My comedy is pretty personal, which should mean it is hard to get a room full of strangers of different ages, races, genders and backgrounds to care about or even understand how I feel, but it’s not. People are people. We are all awkward, afraid, proud and giddy about silly things. So on a very small scale I affect the world thusly: I share private matters that resonate with people, they laugh about them and maybe laugh at themselves, they are entertained and pay it forward by staying in a good mood when buying stamps, and a postal employee doesn’t snap.

Hadiyah: Well I use my comedy as charity by lending my talent to organizations and fund raisers that are making a difference. Each year I perform for Breast Cancer Awareness, Domestic Violence, Alcoholics Anonymous, Education, and more.

Jennifer: I have a little story. When I was in college, I was participating in an activist event — the Day of Silence for gay and lesbian youth. All of the protestors refused to talk for an entire day (we wore buttons so people knew what the point was). And, the day before the event, I innocently asked a woman I knew — someone who was active in the Rainbow Alliance, our LGBT group — whether she was participating, and she said, “No, I’m not doing that. I think you really make change by making friends and building relationships with people and just acting normal, and then when your beliefs come up, your friends see your point of view.” And I found that eye-opening, especially the next day when I was supposed to read a short story aloud in a creative writing class and I declined to do so, as part of the Day of Silence. Was anyone in my writing class a homophobe who needed to be shown the error or his or her ways? Was anyone persuaded by my commitment to the cause? Um, no. I was just being annoying. Another student read my story for me, which kind of defeated part of the exercise, because I was supposed to read it myself. So, yes, I think I could’ve done better by being normal (by which I just mean acting like my everyday self), making friends, building credibility, and sharing my views more organically.

So, I think part of the deal with comedy and activism is that, in order for comedy to work, the audience has to like you or at least see your point of view. You have to build a rapport. If people are already laughing at your jokes — any jokes at all — then there’s a basic foundation in place for actually changing people’s minds, if that’s where the act goes.

Of course, I do see potential for a Day of Silence in comedy. We could mime.

Leah: To be honest, I never thought of myself as a comedienne, but I have always had a die-hard commitment to Damn Good Times. I mean, the way to work through pain is to acknowledge it, accept it, then laugh at it. I mean, I’m a Jew. And I’m Black. And I have HUGE hair. I’ve got thousands of years of oppression behind me, so I had to learn to laugh at myself pretty quick if I was gonna make it.

Also, I’ve realized over the years that people won’t listen to you if you yell at them. If you make them feel comfortable, understood, and safe, they will be more open to discussion. I think humor relaxes people, and can help open doors to communication. I mean it doesn’t work in all situations, but it’s always worth a shot.

3) How do you see comedy as a source of empowerment for women, both in the audience and as performers?

Jessica: I’m thankful to be surrounded by a strong network of some of the toughest, funniest, most ambitious, won’t-take-no ladies around who are to me, an endless supply of inspiration and motivation. Working in comedy is an amazing daily challenge, and that keeps us as performers coming back and pushing back and making strides towards getting what we want and what we’ve earned. It’s also a forum for women to speak frankly and affect change immediately. It keeps the audience returning to laugh, cheer the performers on, be inspired at times, listen and yes, maybe even get laid. By a consenting adult.

Abbi: Great question. They say public speaking is the number one fear of Americans so by virtue of its execution you are facing a fear or watching someone face a fear, which can be totally inspiring, even subconsciously. As a performer becomes more confident in sharing her ideas and engaging people in an entertaining conversation, a stronger connection is made. Young women may feel encouraged to forge a career in the art of stand-up or just emulate what they see and like by translating it to whatever field they’re in.

Hadiyah: Comedy is definitely empowering to women in the audience and I’m reminded of that when I connect with them after my shows. They come up to me and let me know that my jokes say the things they are thinking or wishing they themselves could say and they love it! I’m like self appointed politician winning votes with each show.

Jennifer: If I thought that I personally needed comedy in order to be empowered, I would have my head up my ass to a monumental degree. I hope I’m not so selfish as to believe things like that. I am a recipient of all kinds of forms of privilege. No one has ever tried to silence me. If anything, I have encountered much more classism than sexism in my life. I hope I have, concomitant with the aging process, developed the wisdom to be able to tell the difference between expressing myself and actually doing something of value to other people. I’m sure the comedy experience is different for other people, and my hat is off to anyone who has had to slog through sexism or other cultural barriers to perform stand-up or to be heard at all. If you want to empower someone — someone who actually needs it — go out into the world and become an expert in something, and charge people a lot of money for it, and send the money to a girls’ school in Afghanistan, or to a fistula hospital. If the something that allows you to make that kind of money is stand-up, sweet, but in my experience, stand-up is a really bad way to make money. Comedy might make you and me FEEL empowered, but feelings only exist inside our heads. They’re bullshit compared to action. Money, properly applied, helps people. That’s why this thing is $25.

Leah: Oh, women. Get a bunch of us in a room with cushy chairs, break out the chocolate, and pretty soon someone will start crying. I think it’s important for us to realize that all of our vulnerabilities can also be tools for awesomeness. I know way too many women who let the pressures of life make them feel constantly on the defense, and I want to use comedy and performance art to remind them that embracing our struggles, and learning to love and laugh at ourselves, can make tough days a lot easier. |